Upnor

-

Upnors London Stone

T he London Stones in Lower Upnor are two obelisks (one much smaller than the other) between the Arethusa Venture Centre and the shoreline.

These stone monuments are the London Stone (as marked on OS maps) and were originally placed to mark the boundaries of City of London’s control over limit of the charter rights for fishermen on the River Medway.

T he older stone has the date 1204 carved on it as part of an eighteenth-century inscription.

he larger was erected in 1836 so as to be more prominent and preserve the co-ordinates since the original was badly weathered

The Older London Stone standing in front of the fence of the Arethusa Venture Centre.

The New Upnor Stone

Made from Granite and placed just in front of the old boundary stone, the New London Stone was erected in place in 1836 with the inscription:

Right Hon Willm

Taylor Copeland

Lord MayorJohn Lainson Esq

David Solomon Esq

Sherrifs1836

-

Upper Upnor

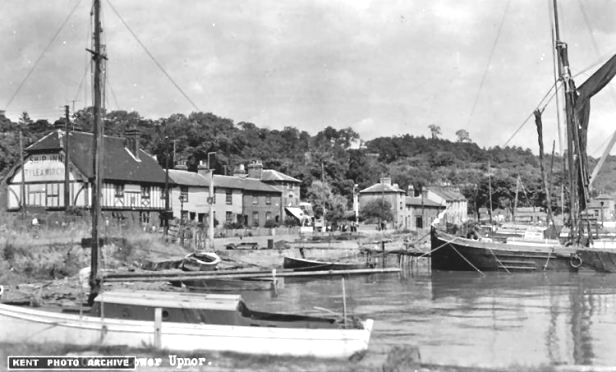

Upper Upnor comprises a village cobbled high street leading down to Upnor Castle. It has many houses displaying Kentish weatherboarding, some are Grade II listed. It also has some terraced streets formerly used by the Ministry of Defence. It is on Chatham Reach directly opposite St Mary’s Creek.

Technically split into two, 'Lower Upnor' and 'Upper Upnor', the castle may be the standout feature. The area is characterised by its cobbled high street ad period buildings.

Upnor meant “at the bank” being “æt þæm ōre” in Old English and “atten ore” in Middle English and “atte Nore” in 1292. However, the meaning changed to “upon the bank” (Middle English: “uppan ore”) and by 1374 it was “Upnore”.

-

The Royal Engineers

The Royal Engineers still have a presence in Upper Upnor; the Royal School of Military Engineering (Riverine Operations section) maintains classrooms, workshops and a hard in Upnor for training Royal Engineers assault boat operators and watermanship safety officers, who continue to operate craft on operations all over the world.

The section operates Mk 1 and 3 Rigid Raiders, and combat support boats, as well as teaching use of the Mk 6 Assault Boat. The area was also used for other training purposes by the Royal School of Military Engineering including practice and test bomb disposal tasks by the Defence Explosive Ordnance Disposal School, until its move to Bicester.

A skeleton of a Straight-tusked Elephant was excavated in 1911, during the construction of the Royal Engineers’ Upnor Hard

-

Upnor Castle

Upnor Castle served as a gunpowder magazine for the Board of Ordnance from 1668, providing powder for the defences of Chatham Dockyard and for the fleet based in the Nore.

In 1810 a new magazine with space for 10,000 barrels of gunpowder was built downriver from the castle (which had long needed to expand its capacity) along with a 'shifting house' for inspecting powder that had arrived by sea (though demolished, its surrounding earth traverse is still in evidence, midway between the magazine and the castle).

In 1856 a second magazine was constructed alongside the first, to the same design, but with more than double the capacity; (this still stands on the river bank, the earlier magazine having been demolished in 1964).

At the same time, buildings were constructed (alongside the shifting house) for storing and maintaining artillery shells; but these soon proved too small, so the site began to be extended to the north, where additional shell stores were built from the 1860s onwards. A little further to the north, a group of large houses were bought to serve as offices for the depot. There was not enough space though for further bulk storage of gunpowder, so in 1875 a separate set of five magazines were built, inland at Chattenden, and linked to Upnor by a narrow-gauge railway. The Upnor magazines were then converted into filled shell stores

The three sites, Upnor, Lodge Hill and Chattenden, were active as Royal Naval Armaments Depots until the mid-1960s. Thereafter they remained in military hands as part of the Royal School of Military Engineering until the mid-2010s. Meanwhile, the surviving buildings to the north were also being refurbished for light commercial and retail use. The inland depots, latterly known as Chattenden and Lodge Hill Military Camps, were put up for sale in 2016.

The castle today

Following the end of the war in 1945, the Admiralty gave approval for Upnor Castle to be used as a Departmental Museum and to be opened to the public. It subsequently underwent a degree of restoration. The castle was scheduled as an Ancient Monument in January 1960 and is currently managed by English Heritage. It remains part of the Crown Estate.

Upnor Castle's buildings were constructed from a combination of Kentish ragstone and ashlar blocks, plus red bricks and timber. Its main building is a two-storeyed rectangular block that measures 41 m (135 ft) by 21 m (69 ft), aligned in a north-east/south-west direction on the west bank of the Medway. Later known as the Magazine, it has been changed considerably since its original construction. It would have included limited barrack accommodation, possibly in a small second storey placed behind gun platforms on the roof.

After the building was converted into a magazine in 1668, many changes were made which have obscured the earlier design. The second storey appears to have been extended across the full length of the building, covering over the earlier rooftop gun platforms. This gave more room for storage in the interior. The ground floor was divided into three compartments with a woodblock floor and copper-sheeted doors to reduce the risk of sparks. Further stores were housed on the first floor, with a windlass to raise stores from the waterside.

A circular staircase within the building gives access to the castle's main gun platform or water bastion, a low triangular structure projecting into the river. The castle's main armament was mounted here in the open air; this is now represented by six mid-19th century guns that are still on their original carriages.

There are nine embrasures in the bastion, six facing downstream and three upstream, with a rounded parapet designed to deflect shot.

The water bastion was additionally protected by a wooden palisade that follows its triangular course a few metres further out in the river. The present palisade is a modern recreation of the original structure.

-

Upnor Castle Pt2

A pair of towers stand on the river's edge a short distance on either side from the main building. They were originally two-storeyed open-backed structures with gun platforms situated on their first floors, providing flanking fire down the line of the ditch around the castle's perimeter. They were later adapted for use as accommodation, with their backs closed with bricks and the towers increased in height to provide a third storey. Traces of the gun embrasures can still be seen at the point where the original roofline was.

The South Towers were said to have been for the use of the castle's governor, though their lack of comfort meant that successive governors declined to live there. The two towers are linked to the main building by a crenellated curtain wall where additional cannons were emplaced in two embrasures on the north parapet and one on the south.

The castle's principal buildings are situated on the east side of a rectangular courtyard within which stand two large Turkey oaks, said to have been grown from acorns brought from Crimea after the Crimean War.

A stone curtain wall topped with brick surrounds the courtyard, standing about 1 m (3.3 ft) thick and 4 m (13 ft) high.

The courtyard is entered on the north-western side through a four-storeyed gatehouse with gun embrasures for additional defensive strength. It was substantially rebuilt in the 1650s after being badly damaged in a 1653 fire, traces of which can still be seen in the form of scorched stones on the first-floor walls.

A central gateway with a round arch leads into a passage that gives access to the courtyard. Above the gateway is a late 18th-century clock that was inserted into the existing structure. A wooden bellcote was added in the early 19th century, and a modern flagpole surmounts the building.

The curtain wall is surrounded by a dry ditch which was originally nearly 10 m (33 ft) wide by 5.5 m (18 ft) deep, though it has since been partially infilled. Visitors to the castle crossed a drawbridge, which is no longer extant, to reach the gatehouse. A secondary entrance to the castle is provided by a sally portin the north wall. On the inside of the curtain wall the brick foundations of buildings can still be seen. These were originally lean-to structures, constructed in the 17th century to provide storage facilities for the garrison.

-

Cockham Wood Fort

Built in the late 16th century as a direct result of the Dutch raid on Chatham Dockyard 1667, the fort originally held 48 guns.

Cockham Wood Fort was constructed in 1669 by Sir Bernard de Gomme on the north bank of the River Medway. It was constructed with a brick base supporting an upper tier of earthworks. It was designed to hold 21 guns on the lower tier and 20 on the upper tier.

In conjunction with Fort Gillingham, it took on the role of defending Chatham Dockyard from seaborne attack, a role which had been performed by Upnor Castle for the previous hundred years. The fort was abandoned around 1818 after several decades of gradual dilapidation.

Within 100 years the arsenal had been removed and the fort had begun to fall into ruins.

Some of its structure is still standing, the most obvious part being the brickwork of the lower battery which is a prominent feature on the shoreline of the River Medway

In terms of schools, Upnor doesn’t have any of its own, but the nearby Medway towns have plenty of primary and secondary schools to choose from. Regular high speed train services run through these towns between London and the coast, with the nearest station to Upnor being Strood.

Upnor’s most distinctive feature is its castle, an Elizabethan fort that played an important role in protecting the dockyard and ships in Chatham in the 17th and 18th century.

Tucked amongst six acres of land, it is a truly impressive landmark to visit and is now an English Heritage property. The castle is closed from November through to March, and requires payment to enter when it is open, costing £7.70 for adults and £3.40 for children. (Prices may change over time)

Upnor Castle was originally built between 1559 and 1567 on the orders of Queen Elizabeth I in order to protect Chatham Dockyard and the associated naval anchorage. It was called into action in June 1667 when the Dutch Navy conducted a raid on the ships moored in the river; the castle proved ineffective in repelling the attack and it was decommissioned soon afterwards.

Though the castle was only operational as a fort for about 100 years, it was retained as a gunpowder magazine and ammunition store until the end of the First World War; continuing in military use through World War II, it was opened to the public as a museum in 1945

Although the castle was an important link in the defence line, it was not well maintained and proved ineffective when the Dutch, under the command of Admiral de Ruyter, sailed up the Medway in June 1667 to attack the dockyard. The enemy fleet met very little resistance and when it left two days later, it had destroyed or captured a large number of the Royal Navy ships anchored at Chatham.

-

The Dutch Raid

Why did it start?

In the seventeenth century, intensive political and commercial rivalry between the English and the Dutch spilled over repeatedly into war. This was an age of empire. Both powers were determined to grow at the expense of the other and maintain access to the market for the foreign luxury goods that sold so well at home.

Maritime security and control of the sea were absolutely paramount. The young Dutch nation had quickly developed with Europe’s most up-to-date fleet of merchant shipping. This enabled them to exploit their military presence in Asia and become a leading commercial power. In contrast, England’s capabilities in the early seventeenth century were in decline. Peace with Spain meant that the navy was run down and money saved. A shortage of available vessels meant that English traders used Dutch ships instead.

In 1651, the English government put a stop to this practice and passed the first of a series of Navigation Acts, which stated that all goods bound for England had to be carried in English ships. The navy was encouraged to police the law by attacking and boarding all Dutch vessels. The first Anglo-Dutch War was the result. It lasted two years. An uneasy peace followed, broken by isolated clashes in West Africa and North America.

In1665, a second war began promisingly for the English, with victory at the Battle of Lowestoft. The following year, a controversial action known as ‘Holmes’s Bonfire’ raised the stakes considerably. A small English force under Rear Admiral Robert Holmes destroyed a large Dutch merchant fleet where it lay at anchor and then landed and burnt the town of West-Terschelling. The Dutch saw the Fire of London-which erupted just a few weeks later-as divine retribution for this action. It was no doubt also in their minds as they sailed up the Medway in 1667.

Who was involved?

During the Anglo-Dutch wars, almost all military action was designed to disrupt and destroy commercial operations. The prime target was always shipping. Large ships were expensive to build and costly to maintain. Each one required a well-trained crew who expected to be paid. The poor morale that affected seamen who were owed wages was a significant factor in many engagements, especially on the Medway in 1667. The English in particular were always short of money and pay arrears in the navy were notorious.

War increased the number of ships built, but also affected their quality. Navies became more standardised. New tactics demanded new kinds of ships. From the mid-1650s onwards, ‘ships-of-the-line’ were needed from the dockyards of both nations. These engaged the enemy in single-file formation, exchanging a massive weight of iron shot with each broadside. Naval personnel were also subjected to new discipline.

In 1653, the English published the Sailing and Fighting Instructions, sometimes known as the Articles of War. These outlined the responsibilities of naval captains, and the punishments that were due in case of failure or neglect.

Peter Pett

Pett was Commissioner of the Dockyard and therefore at the heart of events on the English side. In1667, he made a convenient scapegoat. Diarist Samuel Pepys was with him as he attempted to claim before a Committee of Enquiry afterwards that the ship models he saved would have been more valuable to the Dutch than the real thing. ‘This they all laughed at’ wrote Pepys.

Michiel de Ruyter was in overall charge of the Dutch fleet in 1667. de Ruyter was a Dutch hero who had served in a lifetime of spectacular engagements all round the world. During the attack he remained within the Thames estuary during the first phase of the action, before personally leading the attack on Upnor Castle.

What happened?

On 7 June 1667, a large Dutch fleet anchored in the Thames estuary. This created considerable alarm. A brief attack up the Thames came to nothing, and the English began to look to the defences of the River Medway. These consisted of an unfinished fort at Sheerness, and a great chain stretched across the river as a physical barrier between Gillingham and Hoo Ness.

Further upstream lay Upnor Castle. Charles II appointed the Duke of Albemarle to the overall English command. He gave several orders. He wanted to move English ships further upstream to safety; to sink other vessels in order to block the river; and to find ammunition for Upnor Castle, the guard ships by the chain, and new batteries on the shore. In all this he was hampered by a lack of money and great confusion in the lines of command below him.

.The Dutch attacked the Sheerness fortification and took it easily as the garrison deserted. They then turned their attention upstream. A Dutch squadron approached the chain at Gillingham in line astern at about 10am on 12 June. They engaged the guard ships, and, with fireships blazing, bore down upon the chain. It broke. There was a rush for the English flagship, the Royal Charles. Despite Albemarle’s orders, she remained at her station with a skeleton crew who melted away at the first approach of the Dutch.

On the evening of the 12 June, the Dutch agreed a new phase of their plan. The main thrust would be to engage Upnor Castle while fireships could be positioned alongside the English men-of-war.

In Upnor Reach the next day, the fighting was much more intense. The Dutch nevertheless achieved their objectives and must have been tempted to remain and push on for the ultimate prize of the Chatham Dockyard, but the narrow width of the river, increased casualties, and a lack of remaining fireships, meant that instead they decided to withdraw with the ebb tide on the following day.

What came next?

The English were taken aback by the skill with which the Dutch managed their escape. Samuel Pepys noted the seamanship with which they removed the Royal Charles, heeling her over to reduce her draught, so that she cleared the mud. In fact, she proved too large for use in the shallow waters of the Low Countries.

The Dutch scrapped her in1673. The coat of arms from her stern was saved. It remains on display in Amsterdam to this very day.

Once the Dutch were gone, the English began to salvage their ships - and their reputations. Peter Pett was sent to the Tower.

At the subsequent enquiry, accusations of treason were in the air, but, in the end, Pett was removed from office and allowed to disappear. The charges were dropped. Reform, however, was essential. The English would never again allow such a toxic mix of corruption, incompetence and lack of money to undermine their naval capabilities.

It was the end, however, of the Medway anchorage, although the continued growth of the Chatham Dockyard ensured a strong nautical presence locally for many years to come.

With the departure of the fleet, Upnor Castle became suddenly redundant. Its geographical position saved it from demolition, and it turned into the largest gunpowder store in the country. Access by water enabled the delivery and distribution of the vast amounts of powder required by the ships-of-the-line, and the building’s construction permitted a certain amount of security for such a valuable and dangerous commodity.

The English of course were in no condition to continue the war. A peace treaty was signed at Breda in July. Tensions remained however, and amid considerable political turmoil at home, the Dutch found themselves fighting a new war, this time against both England and France, by 1672. A lasting peace was achieved only with the establishment of a Dutchman, William of Orange, and his English wife Mary, as joint monarchs on the throne of England in 1688

-

The Arethusa Visitors Centre

The origins of the organisation, now known as The Shaftesbury Homes and Arethusa, (one of the oldest surviving children’s charities) date back to 1843, when a young solicitor’s clerk called William Williams, badly crippled in his youth, was travelling to the West Country by train. In the next compartment he heard a commotion and, looking into it, he saw a dozen or so boys in rags, handcuffed together. They were, he learned, to be shipped to a convict settlement in Australia.

Williams was so appalled by this treatment that he formed a committee of friends to found a Ragged School in an old hay loft in the notorious Seven Dials District in Holborn, known in those days as The Rookery. There the committee held a Sunday School and gave destitute children their only square meal of the week.

It was not long before William Williams’ Ragged School project attracted the patronage of the great Victorian social reformer, the Seventh Earl of Shaftesbury. On St. Valentine’s Day in 1866, 200 homeless boys were invited to a supper at the Parker Street Refuge. After a feast of roast beef and plum pudding Lord Shaftesbury asked the boys “supposing that there were in the Thames a big ship large enough to contain a thousand boys, would you like to be placed on board to be taught trades or trained for the Navy and Merchant Services?” A forest of upraised hands settled the matter

When the original Arethusa, which was based at Greenhithe, further west up the Thames was deemed to be in too poor a state to continue, a replacement was sought. In 1933 the merchantman Peking – one of the famous ‘Flying Ps’ – built in Germany became the second Arethusa training ship at a new base which had been established at Lower Upnor. When the first Arethusa was broken up, its figurehead was saved and placed on display at the new base where it has remained every since as a prominent local landmark.

From 1976, the shore base at Lower Upnor was redeveloped as a residential education and activity centre for inner city children known as The Arethusa Venture Centre. Continuous development at the Centre has resulted in a range of modern facilities which now include three modern dormitory blocks, a kitchen and dining hall, a purpose built climbing wall, indoor sports hall and a science laboratory as well as the original, but updated, swimming pool

This Arethusa was named by The Countess of Burma, CBE CD JP DL in July 1982 and began a highly successful career offering exciting and demanding sea-going holidays and adventures for youngsters mainly from backgrounds unlikely to provide them with this type of opportunity.

-

Albert Edward McKenzie VC

Albert McKenzie joined the Royal Navy training ship Arethusa at Greenhithe in 1913. A fine athlete despite being just 5ft 2in tall, he excelled at football and boxing, for which he gained the first of an array of medals and trophies. Having left Arethusa as a Boy Second Class on 20 June 1914, he advanced one step in rank to Boy First Class a week before Christmas. He was promoted to Able Seaman on 23rd April 1916, and served in minesweepers, patrol boats and in convoy escorts before being transferred to the battleship Neptune, part of the Grand Fleet based at Scapa Flow.

He then became one of fifty men to answer the call for volunteers from the Neptune for special service. He was one of eight “Arethusa Lads” to embark on HMS Vindictive to Zeebrugge. All were to be decorated for bravery, seven of them receiving DSMs to set alongside Albert’s VC.

On 22/23 April 1918 at Zeebrugge, Belgium, Able Seaman McKenzie was a member of a storming party on the night of the operation. He landed with his machine-gun in the face of great difficulties, advancing down the Mole with his commanding officer, who with most of his party was killed. The seaman accounted for several of the enemy running for shelter to a destroyer alongside the Mole, and was severely wounded whilst working his gun in an exposed position.

So serious were his wounds in the raid, he was ferried straight from the docks at Dover to the Royal Naval Hospital at Chatham. He was still recovering from his injuries when it was announced in the London Gazette of 23 July 1918 that he had been selected by the crew of Vindictive, Iris II, Daffodil and the naval assaulting force to receive the Victoria Cross. With his mother and sister, he attended on crutches the investiture in the quadrangle of Buckingham Palace on 31 July 1918.

After the ceremony he returned to his mother’s house where he was greeted by the Mayor of Southwark, who held aloft McKenzie’s blood-stained uniform and smashed watch. His mother, who had already lost one son in the conflict, received a gift of War Bonds and an illuminated address.

By the autumn of 1918, the young seaman was still being treated in Chatham Naval Hospital, where his wounded foot had developed septic poisoning, but just as he appeared to be making a good recovery, he fell victim to the influenza pandemic. In his weakened state the “flu” soon developed into pneumonia from which he died on 3 November, just eight days before the Armistice.